MILES O’BRIEN:

"Star Trek" isn't my thing anyway, even though many people think I stole my name from Chief Miles O'Brien on "Deep Space Nine."

Like nearly other advancement in prosthetic technology, the impetus for innovation was war. Better body armor meant soldiers who would have died on the battlefield a generation ago were coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan alive, but often more seriously maimed.

Meanwhile, upper limb prosthetic technology was several wars behind. Wounded soldiers were and still are routinely fitted with a body-powered prosthetic, the design first developed during the Civil War. The split hook is, relatively speaking, a modern marvel, patented in 1912.

Here's how a body-powered upper limb prosthetic works. There's a strap tied across my chest. It is attached to a cable, just like a bike brake cable. When I move forward, it bends the elbow or, if I spread my shoulders out, same thing. If I stop and lock the elbow, those same motions will open the hook, which closes on the force of some rubber bands.

It's confining and clunky, really not much more than a hook on a stick. It's better than nothing sometimes, but not always. The technology had stagnated because it's such a tall order to replace a human arm and hand with its complex, varied mission, and there just aren't many of us, only about 100,000 upper limb amputees in the U.S., compared to a million who have lost legs, big challenge, tiny demand.

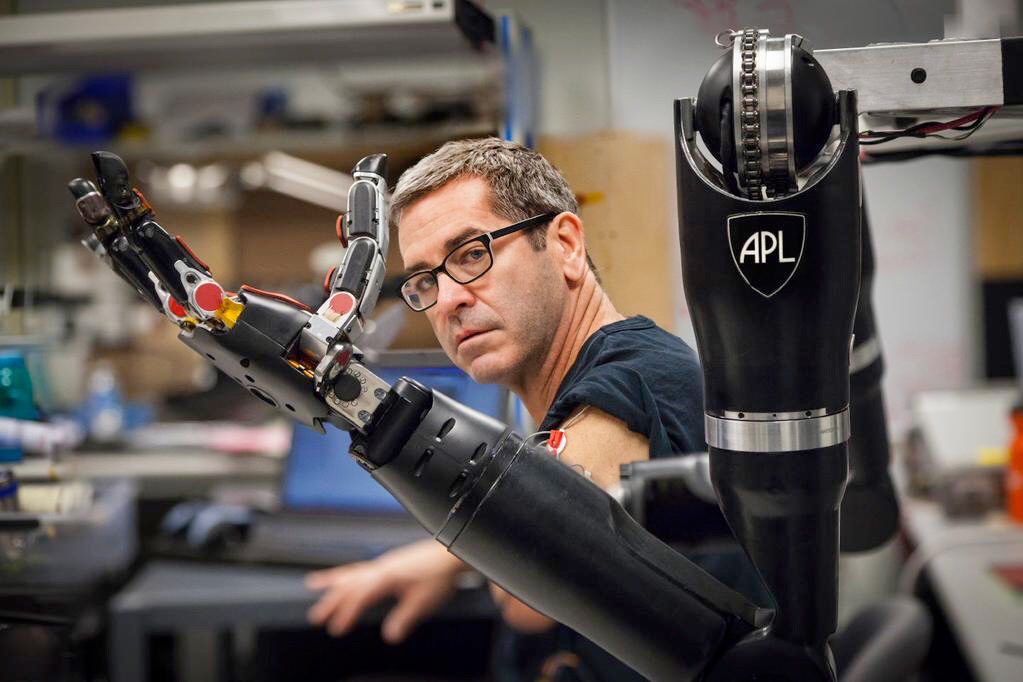

So, in 2006, the Pentagon's research and development enterprise, DARPA, launched its $48 million Revolutionizing Prosthetics program. The Modular Prosthetic Limb is one of the outcomes of that effort. The arm has 22 degrees of freedom and is designed to be almost as intuitive and functional as the one I lost.

Right now, it is still in the testing phase. It won't be available for widespread use for years. But the research team was kind enough to offer me a test drive, if you will.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2ejnby4e9GomaismZh6or7MrA%3D%3D